What makes us remember what we do from long term memory? And what makes us recall those events in the way we do?

Those are the million dollar questions, and scholars and wags have debated these questions for millennia.

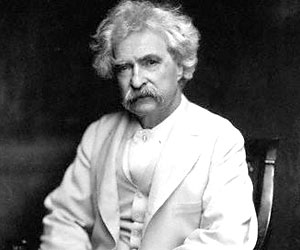

Here are some thoughts from Mark Twain, one of our country’s great thinkers….

“When I was younger, I could remember anything, whether it had happened or not; but my faculties are decaying now and soon I shall be so I cannot remember any but the things that never happened.

” Mark Twain’s Autobiography

First, Twain emphasizes that he seriously doubts the veracity of anything he remembers. Might have happened. Might not. Critical points. Especially if you have to take what you recall to court. This point is extremely relevant.

Twain’s next remark was, to my ears, generated mostly by frustration. It is the same frustration that has plagued many researchers who ponder the questions I raised above.

“Well, certainly memory is a curious machine and strangely capricious. It has no order, it has no system, it has no notion of values, it is always throwing away gold and hoarding rubbish. Out of that dim old time I have recalled that swarm of wholly trifling facts with case and precision, yet to save my life I can’t get back my mathematics. It vexes me, yet I am aware that everybody’s memory is like that, and that therefore I have no right to complain.”

- “Three Thousand Years among the Microbes”

It would have been easy and simple for me, as a young researcher in autobiographical memory, to defer to Twain and close the book on the matter. But I didn’t.

And it is with these cardinal conundrums my voyage into the chaos—so sayeth Twain—began.

Where to begin?

One place is with the earliest memory, another target of interest from serious thinkers.

Freud’s opinion was, invariably, the earliest memory was a screen. For what? Basically for more important material, “hotter” material that lay hidden beneath more benign, bland appearing events. The therapist—here read ‘analyst’—was to break the memory into parts and with great skill seek associations to those various parts and thus cause to rise from the depths of the unconscious memories that were in effect submerged by the screen memory.

Ingenious!

But a problem! If it was relatively easy to call the repressed memory to consciousness by free associations, might the newly un-repressed memory be a screen for something even more repressed and even more laden with negative affect (feelings)? Yes!

And so we find the equivalent of a double cheeseburger in long term memory, with the top paddy holding down a succession of other paddies, each successfully more repressed than the one above it, each laden with ever more negative feelings.

Which leaves us with the troublesome question: If each memory serves as a cover for the one below it, what lies at the very bottom of it all? Such a question! Basically, that is unknowable. Analysis is a process that never ends. What is probable (and we can’t know that) is a group of non-verbal memories, each with strong negative feelings which need to be processed and integrated.

Who else has something to say?

Alfred Adler, the father of Individual Psychology and himself a powerful thinker, had a different approach. He was not interested in what he couldn’t know. He suggested that the first memory revealed the individual’s “style of life” and “degree of social interest”.

I’m certain Adler knew what he meant by both terms, But I have never found a clear definition. So here is what I think he meant. By style of life, I think he meant how an individual conducted himself. His followers tried to neaten that up by describing various goals of life, such as revenge. Those who wanted to get back at others for perceived slights or wrongs recalled memories which featured the actualized goal of revenge. And the degree of social interest? Low in such cases, because revenge was not something that was helpful to society.

There are many Aderians who have spent a lot of energy delineating the Adlerian approach to the first memory, and it is worthwhile to study what they say. But for me personally, I did not find their system helped me that much in understanding why this memory and not that.

Unless you believed that the behavioral goal determined which events were selected and how they were recalled. But Adler did not talk about this matter with much clarity.

After many false starts I intuited that clients brought in early memories (not necessarily the earliest) that explained why they were coming into therapy. Where in their lives they were stuck. Memory being such as it is, a single memory may not telescope the process adequately. One memory, like a broken bottle, may provide a piece of the puzzle. But only the entirely of the pieces, when properly assembled, provides the cause and the effect of the problem so we see ‘because of this, that follows, and here is where I am stuck.’ In other words, the entirely of the pieces approximates the entirety of the bottle.

I made this discovery in the process of assembling several memories for my clients as I had learned early on not to trust anyone memory, such as the earliest, too much. For Freud was correct, at least at times, in calling the earliest memory a “screen”. I, too, noticed that some first memories were incredibly bland, but by the time I got to memory 4, the ‘juicy’ memories began to appear.

But now I became hounded by my own set of questions, as Freud did, as Adler did.

How did I know that ‘the answer’ to the problem lay in a set of memories. And, pray tell, what made one memory ‘juicy’ and another memory not?

Good questions those.

And we will begin the next entry with just those questions.